Archaeology and Connection through Tabletop Games

Archaeologists Play an Artifact Worldbuilding Game and Share Their Work

“I knew a three-year-old’s level of Russian,” Reese shared, laughing at a memory from a past site project.

“I didn’t really need to be able to convey stuff for the job when working with the Mongolian crew.” One night when a drunken fellow walked up to him, “I was just like ‘oh hello, my name’s this, how are you’, all that stuff. And my friend’s like, ‘he speaks Russian’. So for the rest of the project they always talked to me in Russian. I didn’t know what the hell they were saying. They knew I was really bad at Russian, but they were still trying to communicate which was nice.”

“We rolled up somewhere, and I went in to buy beer. I’m saying ‘shto pivo, shto pivo,’ Someone says something back and I don’t know what it means. And like, eventually our driver goes, ‘he means this.’ And I’m like - you’re speaking? It’s been a month and a half, and you’re speaking English now?” Turns out all of them spoke completely fine English but they were just shy.

Stories like this capture what excites me about archaeology aside the historic discoveries themselves: moments where miscommunication, persistence, and a bit of humor create really easy bridges between people, both past and present.

A few years ago, I tried to channel this spirit by creating To Care is to Cairn; a tabletop worldbuilding game that explores the history of civilizations through the lens of artifacts, born also from a small obsession with how material culture is reinterpreted and reappropriated.1 In 2024, it was showcased by Jacqui Lokum and Lucy Arrell at the New Zealand Archaeological Conference. This year, I now intend to use the game as an overly-convoluted framework to interview archaeologists about exciting moments from their careers. As they played to create a fictional history, we discussed what parts of their real-world work was influencing their creative choices.

I hope you enjoy the archaeologist’s stories of connection to place, time, and people, and I deeply appreciate the time they lent me to play a little bit of make-believe.

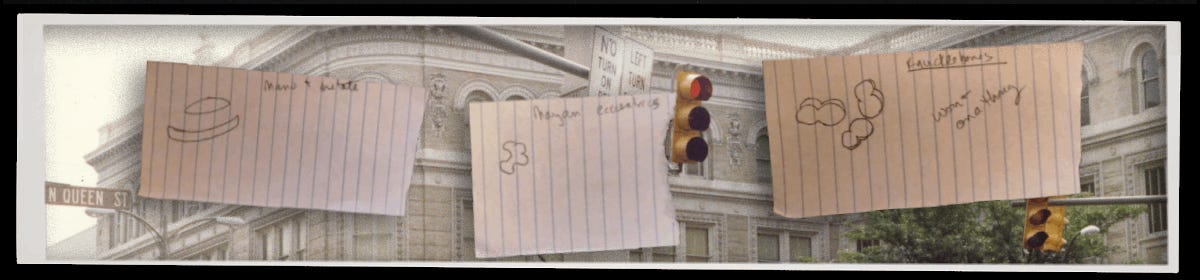

Reese, John, and Christina, are all archaeologists working in Cultural Resource Management (CRM), which involves identifying, evaluating, protecting, and managing historical and archaeological resources in the context of development and land-use projects. They began the game by sketching the contours of their fictional world: rivers winding down from high mountains, forests pressing close, and a central confluence where life could take root. They agreed to start their civilization in the hunter-gatherer period, with seasonal camps scattered across the landscape rather than permanent settlements.

Reese, who has extensively studied the Bronze Age within Mongolia, referenced his understandings of center-Asian societies where “depending upon the area a lot of tribes would have moved seasonally. Sometimes if the area is really nice, you know maybe like every spring like to summer to winter, they would entertain different camps.”

A diamond marked the main encampment at the river junction, while smaller circles marked temporary base camps and resource sites: lithic quarries, fishing spots, and foraging grounds. The players added on ideas of territoriality, animal management of the salmon run, and how pastoralism could emerge.

The civilization’s early lore centered on three artifacts: pitted river stones believed to carry bad luck, knuckle bones used for gambling, and a blue crystal brought back by a young hero.

Ethnobotany

the interdisciplinary study of the relationships between humans and plants, focusing on traditional and indigenous knowledge of plant use.

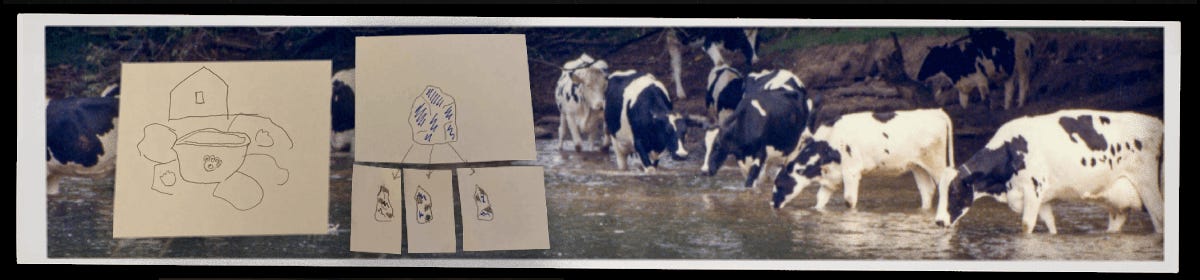

As the river ran low and gameplay began, Christina chose to incorporate the river stones into a grindstone set known as a mano and metate - a pair traditionally used for grinding seeds and grains into flour, “They’re going to be looking more at the grains, the tough foods, the ones that they don’t normally eat because they’re a pain to process.”

Much later in the game she would add, “I’m trying to figure out how to make the knuckle bones useful, but I guess they’re digging out their old manos and metates. The floods really disrupted normal food production and gathering, so they’re going to have to go back to the foods nobody really wants to eat, but you’ve got to eat something.”

Christina then referenced and pulled out Native American Ethnobotany, by Daniel E. Moerman, an encyclopedic catalog of plants and their traditional uses. “It has a whole section on famine foods, starvation foods,” she explained. “I’ve been looking for something like this.”

Nelumbo lutea

…Dakota Soup Hard, nut-like seeds cracked, freed from the shells, and used with meat to make soup. Unspecified Peeled tubers cooked with meat or hominy and used for food. (70:79) Huron Starvation Food Roots used with acorns during famine. Roots used with acorns during famine. (as Nelumbium luteim 3:63) Meskwaki Unspecified Seeds cooked with corn. Winter Use Food Terminal shoots cut crosswise, strung on string, and dried for winter use. (152:262) Ojibwa Unspecified Hard chestnut-like seeds roasted and made into a sweet meal. Shoots cooked with venison, corn, or beans. The terminal shoots are cut off at either end of the underground creeping rootstock and the remainder is their potato…

- Excerpt Example from Native American Ethnobotany

As Christina was fetching the Ethnobotany book, John started talking about his recent return from the American Southwest, where the dry desert preserves artifacts almost effortlessly. “I’m derailing of course, but that was kind of the point of today.” He was absolutely correct about that. “It was an amazing trip. I recommend anyone that can get out to Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde to do so. The thing that really got me was: I was out there, and I thought, holy crap, this is archaeology on easy mode. There are only about ten main species to keep track of, and they’re all really recognizable. Yucca fibers for instance were used for clothing, and we still have preserved examples. Or there was the wood in the great houses, usually just one of three species.”2

By contrast, he said, work in the Northeast could feel impenetrable: too many species, dense vegetation, invasive plants, and the constant challenge of telling one thing from another. When Christina returned, the conversation shifted back to the Southwest, where Christina’s “favorite overly obsessive dating method” had first been developed: dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating. “They were able to do it in the Southwest because wood lasts forever out there. You can line up rings from ancient buildings and boats with modern tree samples, and find where the records overlap.”3

“Paying attention is a form of reciprocity with the living world, receiving the gifts with open eyes and open heart.” ― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

On a tour of Chaco, John recalled, a leading dendrochronologist explained how he discovered that some of a building’s dates were off. “There was one part of one of the great houses where he realized the National Park Service, after taking over and stabilizing the site, had used wood that was displaced by a flood. That wood was stacked and later worked into the reconstruction of a different great house.

“The only reason he figured this out was because he asked someone who had been there at the time. They told him, ‘Oh yeah, that wood that washed down, they just kind of stacked it over there and reused it.’ That’s when he realized, ‘That’s why my dates aren’t lining up—it’s not wood from this pueblo at all.’ He said, ‘I would have never known that otherwise. I’m one of the few people who knows the dates coming out of that rebuilt section are wrong, because the beams came from another great house.’ That’s wild.”

Christina additionally brought up a subcategory of ethnobotany, abortifacients, otherwise knowns as plants used to induce miscarriage. “It makes me think that could be how hunter-gatherer women managed to space children about four years apart.”

“That’s related to one of my favorite Roman facts,” John added. In the Mediterranean, a now-extinct plant called silphium was used as a remarkably effective form of birth control. “The Romans literally used it to extinction.” 4

Had anyone worked at a site where nature, aside from plants, affected their work? The question itself came after a player had a cat wandering across a workshop, with unfinished clay dishes waiting to be fired. A paw print was pressed into a bowl.

“Unfortunately, I have nothing romantic to say about it—just terrible amounts of pests and bugs,” Reese replied, “I mean yes, in the sense that horses are of utmost importance, and a lot of the cultural landscape surrounds horses and cattle, but as far as my day-to-day work, no.”

“I have a surprisingly positive one,” Christina offered. “A lot of archaeology deals with rodent burrows and all of that. Out east we mostly do shovel tests for surveying and digging a hole every so many meters or feet. I don’t know why New Jersey uses feet; this is a separate rant of mine. You have to buy a whole new engineer’s ruler just to work in the state. Anyway, everywhere else reasonably uses metric. Out east you dig holes, every 15 meters or so, to see if anything’s in there. Out west however, since there’s less plant life, you can do walkovers. You line up 15 meters apart, take a compass reading off a tree, walk toward the tree, and scan the ground. Rodent burrows and tree falls are actually really nice and convenient for surveying, because they’re excellent places to see if any artifacts have popped up from underground, thanks to them.”

John continued the conversation, “My animal story isn’t one of the fondest memories from my early field technician days. We were doing a farm site in Pureland, South Jersey, an old farmstead with the house still on part of the property, that was being turned into a warehouse. We were doing shovel test pits. I’m in the back because one of the tests falls within the manicured backyard. In a bushy area, I look down, and there’s a foot stone with two initials. We came back, did GPR [Ground Penetrating Radar], found there was a grave-like anomaly, and had to determine if it was human. I wasn’t there, but my crew chief told me: they dug it up with a backhoe, found a burial trench, and a sealed stone box with about a foot of water in it. My crew chief Adrian had to glove up and go into the muck. After all that was done, we found out it was a dog. Apparently, the previous property owner had a dog, and this dog was named Tippy. Tippy was well loved, so they took an old stone septic box and buried Tippy in a sepulcher. They also loved Tippy so much, and apparently their second dog was named Tippy Two. Tippy Two was found close to Tippy One but buried in a cooler.”

Negative Space

emphasizing not just the subject but also the empty space around the subject.

In-Game Prompt: ‘Something gets spoiled and somebody gets blamed’

“That’s a hard one,” Reese began. “I think as food becomes spoiled they’ll collect as many [negatively-associated stones] from around their areas as they can, and they deposit them in large piles far on the fringe”

After further discussion regarding the prompt John added in, “We tend to look for sites, but having an area with no sites at all tells you something—either that, for some reason, that site is not being visited, or is being kept clean. A lot of sacred Native sites are like that, where you may see blank spaces that aren’t blank because nobody did anything there, but because it was reserved for special occasions or special reverence.”

Reese responded, “Excellent. Yeah in the nomadic tradition, with the idea of a bonding mentality and sacred space, you’ll often find for some people they see areas as taboo. Maybe there’s a central feature, like a monument, but around it, it’s clear of stuff because that land belongs to the inhabitant of that monument; they can’t interact with it. You see that perhaps in evidence of camps, which are within a certain range around it.”

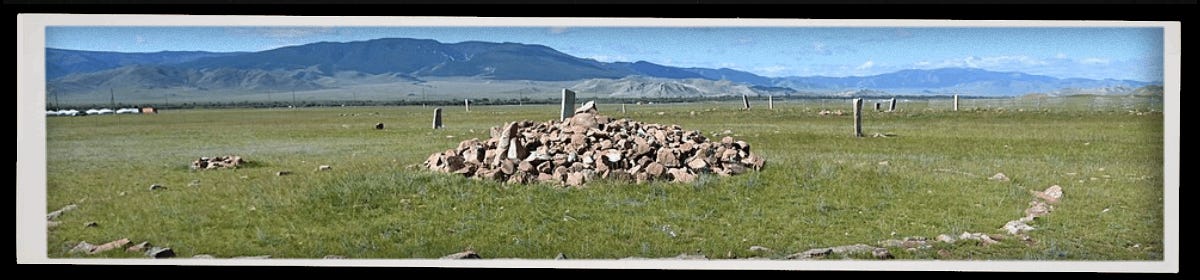

When asked more about his work, Reese replied, “the coolest thing I did was that time in Mongolia - I won't get too long winded about the subject of monumentality - but there are these big cairns called khirigsuurs. It takes so many people to build them and Bronze Age, Mongolia didn't have a whole lot of people. They additionally sacrificed a lot of horses there. So we're digging up all these old horse remains so we could do isotope analysis.”

Click here to view photos from the Western Mongolia Archaeology Project. Reese contributed to the project by surveying steppe and rocky terrain, recording and mapping sites, excavating burial features, analyzing human and animal remains along with artifacts in the lab, and entering survey and artifact data into the project database.

Finally, on the topic of negative space, John offered another example. “If anyone’s been to Red Bank Battlefield or knows Dr. Janofsky from Rowan, she gives a fantastic lecture on that topic—how monumentality in the park developed, particularly with African-American presence at Red Bank, which was systematically erased by white historians. Black families came back to the park with records of parents and grandparents in the battle”, which was in contrast to the written history that the battle was one of only white soldiers. “The monument at Red Bank is the stereotypical white colonial soldier, made not by that community but by people rewriting history.”

“We have applied to re-do the monument in 2026 and right a wrong,” said Red Bank Battlefield Director Jennifer Janofsky – a history professor at Rowan University – during a Family Day tour on May 18. “We have also applied to be recognized on the New Jersey Black History Trail.”

“There were at least 48 Black and Native American participants in the battle and as many as 56,” she noted, citing a study in 2014 by historian Dr. Robert Selig. “They were members of the integrated 1st and 2nd Rhode Island regiments.”

Symbolic Changes

“That’s my protest sign right there, with the red, white, and blue”, John pointed behind him in the Zoom call, “One of our designers made it. And we wanted a way to reclaim the flag as a patriotic symbol.”

Weapons of a tragic war can be melted into a grand statue, reinventing the power they give to the people. The symbolic meaning behind one or more of your artifacts has been transformed. The most recent event has forever changed how well see its history, and how it may be used going forward. This action can give or take away the power an object or symbol holds over future events.

— To Care is to Cairn, Change Symbology Action

“I mean, the big thing is, at least for me, and I know for a lot of people I know, there’s a little bit of a cringe that happens when you see someone displaying an American flag on their truck or their home. It’s almost like a, uh oh, you assume that’s a type of person in this day and age happy about this sort of thing [happening in the government right now]. When I see that flag, my first reaction is how I don’t want to associate with that idea.”

“I think part of the reason people have been talking about reclaiming the flag as part of the protest is to re-grab that association and change the symbol—from a negative one, or one that’s viewed in certain circles as negative, to a positive. Or at least as a way to say: we’re not an ‘other.’ We’re part of this.”

“And I display it at the events upside down, as a symbol of distress. I talk about that to our attendees and say: In maritime history people would fly their flags so you knew who you were dealing with. The upside-down flag was a way to communicate distress, to say we need help. So we’re not flying it upside down out of disrespect right now, but as a call to action, a call for help, and a reminder that, hey, some of this stuff happening right now isn’t normal.”

The Looter’s Museum

Earlier in the call, John shared some of his background in archaeology, “My original interest was in the Neolithic chambered cairns and monumentality in Orkney. Then I did archaeological science as my master’s, basically stealing all the equipment from the chemistry people, multi-million dollar machines, and using them to study ancient garbage.

I came back to the States, which is a much longer story, but I came back and looked for work in CRM. I ended up with Richard Grubb and Associates (RGA) in New Jersey and have worked my way up from there. Right now, I’m a project manager at RGA. I work all throughout New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, et cetera. I also work part-time at a small museum in Cumberland County that nobody ever visits by accident, the Alan Ewing Carman Museum of Prehistory. It has a phenomenal pre-contact collection that was unfortunately built by a looter.

It is exactly what you think of when you picture a looter’s museum: thirty-two grooved axes in a case, frames of points with no rhyme or reason, and we even have a dog burial, which is its own ethical problem.

My good friend Richard Adamczyk is the curator, and I’ve been working with him for the last few years to modernize the space. They are building a new museum, and we have also built a relationship with the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape, a state-recognized tribe. One of my recent projects, last year, came from a museum guest who tipped us off about a threatened site along the Cohansey River. He had seen looting holes on Fish and Wildlife land. Rich and I went out, looked at it, and said, yes, there is a site here. We found artifacts on the surface, looting pits, utilitarian ceramics, flakes. Definitely an encampment. But it was also on a bluff eroding into the river, so it was threatened.

We proposed a pro bono rescue excavation of the site in partnership with the Archaeological Society, the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape, and the Cumberland County Historical Society. That went through DEP, Fish and Wildlife, and SHPO, and it was done. The fieldwork was wonderful. The problem now is that the federal tribes are upset because they do not recognize the state tribes, and SHPO has not been corresponding with them the way they want. It was a wake-up call. You hear in school that all archaeology is political, and you think, I am not in xyz place, don’t worry about it. But then this happens.

The feedback we got from the state-recognized tribe was really powerful. We are doing our best to navigate those relationships; to meet the federal tribes and say, we understand where you are at, but our hands are tied, and we cannot get into the discussion of who is and is not Native. They want us to denounce and stop working with the state tribe, and we cannot, because they are on our board. That is really challenging.”

“Another favorite project of mine” John continued, “was going back to Orkney two years ago to participate in the excavations at Blomar Chambered Cairn, a recently rediscovered Maeshowe-type Neolithic cairn with in situ remains [remains or objects found and studied in their original location]. I was one of the few professionals on staff who was not a student. At one point an osteoarchaeologist [an archaeologist who studies human and animal skeletal remains] called me in to help, and I spent a week working with human remains. It was the most humbling and nerve-wracking fieldwork I have ever done, exhuming individuals who died 5,000 years ago, trying not to screw it up, and realizing I may never again work on something more significant than what was in front of me at that moment.”

“That’s beautiful, dude,” Reese responded.

Cairns and Potshots

Participants were setting some solid foundations to the world, and how the community reacted and changed due to environmental conditions. Per the name of the game, the subject of Cairns (‘mounds of rough stones built as a memorial or landmark, typically on a hilltop or skyline’) came up as residents of the fictional civilization traveled and lost various objects in surrounding regions.

“For the cairns,” Christina started, “there’s really not much you can do to date them, because it’s just a pile of rocks. We might check for lichen underneath—pick up the top rock and see if there’s lichen underneath. Theoretically, the lichen would die at some point. Other than that, dating a cairn site is basically about trying to find anything else in the area and seeing if you could find a projectile point. We have chronologies of those, so we can say, “Okay, this was here, so probably related.”

“I have a fun story like that.” replied John, “I was doing a job at High Point State Park in North Jersey. They were putting in a bathroom facility, so we did a Phase One survey. It was a limited footprint, and we didn’t find anything, even though it was theoretically moderately sensitive for pre-contact. The only things present were a modern parking lot and an old field stone wall. The area we were working wasn’t a historic occupation site; it was just connected to a 19th-century farm.

On top of that wall was a giant cairn. Apparently, someone had worked with the Ramapough Lunaape, and there are stone cairns in that area of New Jersey registered as pre-contact, Ramapough-associated ceremonial sites. My bosses were freaking out: ‘What do we do about this cairn?’ I said, ‘Oh my god, it’s built on top of a 19th-century stone, so we’re good. It’s definitely not pre-contact.’

The other concern was, ‘Well, what if it was made by a Native person coming to visit the mountains here?’ We didn’t know. We tried talking to the park staff. Eventually, they said, ‘We don’t know who did it; it just kind of showed up one day, seven years ago.’ It was just a bit odd.”

Christina kept the ball rolling on cairns, “Wyoming had a sheep herding tradition for a long time. There were actually Sheep Wars between the sheep herders and the cattle ranchers. It was a whole thing, but it continued into the 20th century. I have it on authority from somebody who went out with some of those sheep herders when they were a kid: some of the cairns that are recorded and have their nice little site numbers and everything on them, were actually built because it turns out sheep herding can get really boring, to the point where stacking random rocks sounded pretty entertaining.”

Reese added in his story to the cairn pile, “It’s funny just talking about all the stacking rocks. In Mongolia, it is a tradition to continue stacking rocks. There are no physical boundaries or territoriality, or at least, not in the way we think. Mongolians have a belief in Nutag, which means “homeland.” A homeland can belong to a human, or to their animal, and instead of encompassing a physical boundary, it’s centered upon a site of belonging. To commemorate the nutag, they will erect a new cairn. Usually, a family that frequents a camp a lot will have their own nutag stone, and they’ll raise other cairns around themselves. It’s really beautiful.”

“Through the way in which herding families, horses and other species that make up this hybrid herd community, live an interconnected co-existence. These concepts tie in not only with a tethering to one’s home, but with a form of multispecies mobile pastoralism, which involves a particular way of managing, nurturing and caring for free-ranging herds, and I would argue is an integral component of a diverse and healthy grassland steppe ecology.”

— Nutag: Homeland to Horses and Humans in Mongolia, Australian National University

A spear-tip artifact was broken with pieces of it lost throughout our session, as a result of various fictional hunting trips. John reflected on a recurring challenge in CRM practice, particularly when working with Lenape sites. “When you find isolates, you could find a perfectly tipped point that you can narrow down to a couple hundred thousand year window. You know the period, you know the rough stage of what was going on when this was theoretically built and the cultural trappings. But, oftentimes you just find that one artifact, and the most common interpretation that even I tend to make is when you find an isolated point somewhere: It's a hunting loss, or someone dropped it inadvertently. You just so happen to put your shovel test pit in the exact lucky right location 2,000 years later, but you're not near the settlement, or the settlement is 2,000 feet that way where you're getting the FCR [Fire Cracked Rocks, which have been altered and split as the result of deliberate heating] and your flakes [portions of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure].

You're like, did someone just take a potshot at something and lose it?”

John, emphasized both the pragmatic and speculative possibilities: “To me, I like the idea of the found isolate and someone seeing a deer or something 200 yards out that way and going, ‘I can hit that,’ and then missing. But I also find the idea a little bit too Occam's razor sometimes. Like Reese was saying, you have situations where there's more intentionality behind the loss of something.”

During this portion of the game, while there were spears that would simply be thrown and lost, numerous negatively associated objects have purposefully been circulated outside the community’s range. At first, participants deliberately sought to dispose of these items as far from the settlement as possible. Over time, however, this practice evolved into an annual event, eventually taking the form of a competitive sport in which runners raced to carry and deposit objects as far as could be.

“The fact is that it might be too easy of an explanation—to say ‘it just got lost and there wasn’t some other purpose’. The bog bodies are the biggest counterexample of that, but we kind of know that there's all this rituality and intentionality there because of the way that it's found, in the place that it's found. There are gaps in accounting for humans being humans, acting weird, superstitious, or just idiosyncratic.”

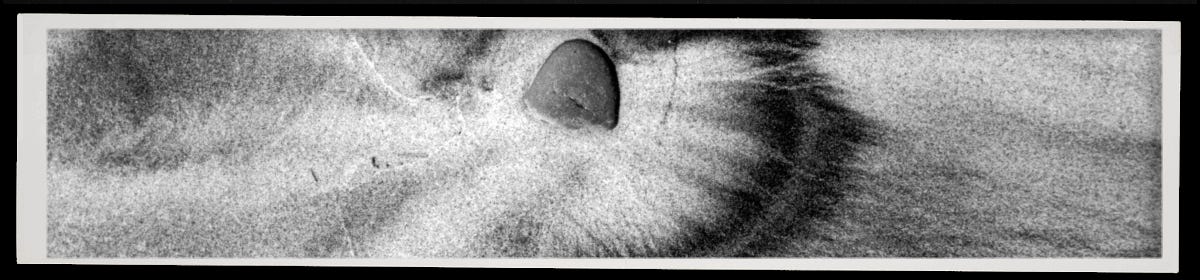

Christina followed by recounting what she described as her most memorable find. “My favorite artifact I've ever found: I’m working on a multi-component site. Basically, as soon as the glacier melted enough, people moved into this area. It’s still an area that's in Jackson Hole, so billionaires live there now. It’s beautiful. I was in a one-by-one unit off by myself digging, and there was nothing in there. Nothing. By this point of the day, we knew where the occupation layers were, and I got past those without finding more than a handful of flakes. It was very sad, and my boss kept coming over and apologizing to me and was like, ‘You just got to finish this for the paperwork, and then I'll get you something better.’ And I was like, ‘That's fine. It’s okay. I’m used to this. I worked in the East a lot; we never found stuff out there.’”

“So I dug, and I dug, and I dug. I finally got to the very bottom of the river that we were next to, originating in the Paleolithic. I got to the bottom, and it was just river cobbles and sand.” Looking closer, Christina saw, “There, in the middle: half of a biface. It was a Paleo-Indian biface; an arrowhead or any stone artifact that’s been worked on both sides. A uniface is a scraper and would only be worked on one side. This could have been a spear point; it could have been a knife.”

Specialists on the team immediately recognized the context. “The magical guys on my crew knew that it was broken during production, which is not rare for Paleo-Indian stone tools. These were the most difficult flint napping techniques that you can think of. There’s a theory that Clovis points [distinctive, fluted spear points created by the Clovis culture] might have had a ceremonial function.”

John was holding up and demonstrating an example cast while she continued, “I didn't see the fluting on it, but otherwise it was this beautiful point, broken in production, and it was found in the middle of the riverbed. I love that—first, because I had found nothing at all, and this was like dead center of my test unit, so that was some luck right there. But I also loved it because the story that immediately came to mind was that this poor person who was flint napping was near the end of making this beautiful project, a stone tool, and it broke. Out of frustration, they may have just chucked it into the river.”

Alternative interpretations remained possible: “It could have been more ceremonial, because, like I was saying, the production of Clovis points is so difficult that people think there might have been a ceremonial or maybe fortune-telling kind of component to it. A good third of them broke during production, which is insane! That is a lot of tools to lose.”

“Just for context,” John held forward his casting, “You have to prepare the entire process just so you can knock that channel out. It’s a work of art.”

“They get huge sometimes too!” Christina exclaimed nodding with John, “which gives them an even higher chance of breaking. It very well could have been a ceremonial type of thing, maybe it was broken on purpose and put in the river on purpose. But I also like the connection with the mundane and the everyday. They had the same emotions as we do. A lot of their individual, daily motivations were different, but the big ones were always still there. It was still always about food and social stuff. I really like that.”

Affordances and Reflections

In the deserts of the North American West Coast, history describes a Klamath/Modoc boys’5 initiation rite in which youths pushed themselves to exhaustion; running across the sand with heavy stones, fasting, and enduring visions in isolation. The practice left behind a scattered grid of cairns, now understood as part of a larger ritual landscape. Nearby, Fern Cave preserves paintings thought to record those vision experiences.6

After Christina shared this history from her trip to Fern Cave, and as a blue rock in the game shifted in symbolism, Reese elaborated, “Meaning-making is central. I’m a big proponent of actor-network theory, which holds that objects and people, within their environments, communicate meaning through their interactions. The reason you choose two different locations or places of notable exchange is because something in that environment signals that it’s special. A special location deserves a special item. That’s what we call affordance”, where we pay attention to what an environment offers the organisms and how they perceive it and act accordingly.7 “The classic example: what’s a chair to you? A chair is something to sit in because of your repeated exposure and experience of using chairs. But you also intuit, through similar experiences with similar objects, that you can stand on a chair, put rocks on it. It can hold things.”

“Moreover, certain information can also be derived from association and internal categorization. This can be exemplified by a post-box, which affords the posting of mail, while a similar looking litterbin does not, hence implying that a post-box has affordance that is ‘indirectly perceived’ (Knappett 2014, pp. 44–45). This means that people do not act directly upon the environment but through the medium of cultural representations.” — Sand-Eriksen, 2023

As we closed up the session, I initiated the final Stratigraphy portion of the game. Any history not captured through artifacts or oral and written accounts was considered lost. Participants reflected as imagined archaeologists, accounting for where these objects might have ended up and how future generations could misinterpret them. Among the recovered artifacts were netting dispersed across a riverbed, knucklebones reworked into worry stones, and statues memorializing “long flowing hair to signify the running speed [sport participants had] flowing up behind them, focusing on dynamic movement.”

Christina shared how this final act underscored the difficulty of archaeological dating in contexts lacking clear stratigraphy (‘the study and interpretation of the soil layers (strata) at an archaeological site, used to reconstruct the history of human activity and establish the relative ages of artifacts and features’). In the game scenario, chipped stones deposited annually could, in theory, be dated by stylistic change, but their later retrieval and mixing erased that easy order. In real-life, a Great Basin woman Christina met who was born before the region was conquered, once who shared that arrowheads were not always being continually produced but rather collected again for reuse, suggesting that modern typological dating may at times reflect patterns of recycling rather than original creation.

Meaning-making and interpreting thought hold an interesting intersection in Tabletop Roleplaying Games (TTRPGs). Games involve subjective processes through which physical materials are transformed into narratives about human experience. Dice, cards, maps, and embodied play bring these personal abstractions into a kinetic form of storytelling. They bring people into a world they’re not as familiar with, while still allowing them to add parts of themselves to it. We are free and bound by our interpretations.

“A lot of games I've played with an archaeology portion or focus”, Christina wrote in an exit poll, “tend to be about finding things, whether a single impressive artifact or a collection that you donate to a museum like in Stardew Valley. I really liked that this one focused on contextualizing the artifacts and placing them within a cultural framework. Don't get me wrong, finding something cool is amazing, but the really interesting part to me is being able to use the things and their context within the landscape and in relation to other artifacts, to understand something about how people lived in the past. That's what archaeology is really about. I thought things got really interesting once we had the cap of three artifacts in hand. I would've happily continued to make new artifacts for each event, but the point really is to consider how an individual object is changed and recontextualized over time.”

John additionally wrote on a kind of recontextualization in his poll, “One of the most memorable moments for me was the interjection of cats and the idea of humor and happenstance/chaos into the mix. We tend to boil history down to logical choices or responses to situations in the past and have difficulty thinking about how humans and their responses aren’t always logical. I think this game helped explore that facet of archaeology well with its creative and collaborative structure”

In this project, we utilized To Care is to Cairn (TCTC) to capture stories of a profession and highlight aspects of archaeological practice. It is however important to acknowledge the limitations of game design and the backgrounds in which we come from. Much like Matrix Games, which once distilled the insights of war experts into tables for strategists, the voices participating inevitably are constrained to what histories are preserved and how they are interpreted. We can recontextualize only as far as our backgrounds allow us. The affordances and nuances behind human history are severely limited by the voices sharing this history and their own individual history.

Expanding on this, John's comments included how “TCTC was an interesting reflection on material culture and processes that to me, worked in reverse from what I’m used to — as an archaeologist we’re used to finding things and trying to work backwards; where did it come from, who made it, what was it used for, why did they buy or make this instead of something else. TCTC however, forced you to treat that deductive process and questions backward.

In terms of bias I’ll fall back on my earlier answer, where many archaeologists, especially those who were brought up in the processual school of thought, can over analyze and look for pure logic in how people made things, lived, and behaved I the past, but it’s never really that simple.”

“There were moments where the collaborative nature - sometimes in tandem or with a conflicting vision - did a good job of introducing that communal perspective through the lens of a TTRPG and collaborative storytelling. Sometimes as professionals we can work in our own silos and forget our implicit bias. Having moments where you can brainstorm with colleagues who have different experiences, training, and perspectives then you do can lead to really interesting and breakthrough moments in research. TCTC does a great job of fostering that within the lens of a tabletop roleplaying game.”

These biases in gameplay are allowed because they let us dip into each other’s fields and worlds a little bit, but we still have to acknowledge we are only capturing those specific, individual experiences.

Christina added on to the suggestion regarding minimizing monocultures when playing in an educational setting: “Perhaps there could be some pre-made artifacts related to a specific culture and/or time period that players can pick from to start, if the purpose is to educate about a specific culture's archaeological remnants. Something like that may also help to encourage people to think about other cultures and times than the ones they may be most used to.”

John added to this point, “I think some structure to the final stages of the game / the stratigraphy discussion, would be a good place to spend some attention - the educational aspects I feel rely on this reflective end to the game, where it forces the players to really grapple with archaeological ideas and the imperfection of the material record. Maybe some guidance questions would help. (In my opinion, like a good anthropology course that rewires how you see yourself and the people around you, this game should challenge your perspectives and leave you with an impression of ‘huh… I never considered that’”

This has been an excellent journey, and I am deeply grateful to Reese, Christina, and John for sharing their time, anecdotes, and ideas. I hope you enjoyed these stories as much as I have. This article is actually the first of three — two more groups of archaeologists will be contributing their own imagined histories. Please stay tuned as each group has new history to bring to the table.

Thank you for Caring to Cairn.

Credits

Participant information (such as name and position) was included in a fashion specifically requested by the individual. Participants additionally were provided an early draft version of the article to help correct for accuracy.

Unless otherwise noted, all images in this article were either maps and artifact cards from the game, photos taken by Kai Medina, or scans from originals photographs by his grandfather, Pierre Giroud.

'The reappropriation of material culture' is the act of taking physical objects or artifacts and then redefining or using them in a new way, often by a different group or within a different context. This process can involve reclaiming symbols, styles, or objects that were previously used to marginalize or oppress a group, or otherwise it is just simply the way objects move through history, picking up intentions and misdirections along the way.

More on dendrochronology’s history: https://www.nps.gov/tont/learn/nature/dendrochronology.htm

They additional used it for other medicines and recipes: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170907-the-mystery-of-the-lost-roman-herb

These are two different but closely related First Nations groups, but the source material I used to fact check this story does not separate them in its descriptions when it comes to this practice.

HAYNAL, P. M. (2000). The Influence of Sacred Rock Cairns and Prayer Seats on Modern Klamath and Modoc Religion and World View. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 22(2), 170–185. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825729

Sand-Eriksen, A. (2023). Exploring Affordances: Late Neolithic and Bronze Age Settlement Locations and Human-Environment Engagements in Southeast Norway. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 56(2), 180–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2023.2262463

Nice